Part Two – A Wedding Gift

This is the second part of an essay on the Schulz Clock by Liza Kroeger that we are publishing in instalments. Read the introduction here and the first instalment here.

I came to learn that the Schulz clock had very proud beginnings. It was commissioned in 1893, by the father of the groom, as a wedding gift for Anna Zacharias and Peter Dietrich Schulz. And it brought together two proud families, the Schulzes and the Zachariases. For an explanation of how German speaking Mennonites like the Schulzes and Zachariases came to Russia see Once Upon A Time. To appreciate the legacies of the Schulz clock and the period of Mennonite history it captures, it helps to understand Peter and Anna’s family history.

“Invitation

God willing, next Thursday, on the 10th of this month, the betrothal of our daughter Anna with the young man, Peter Schulz from Osterwick, shall be celebrated in a Christian manner and to this celebration in our home you, our dear friend, and your cherished family, are warmly invited for 10 o’clock on the day aforementioned.

Respectfully, Anna & Isaak Zacharias Zachariasfeld, 5 June 1893”

Invitation to Peter and Anna’s wedding, 1893.

The Schulzes

The father of the groom, Dietrich Benjamin Schulz, had apprenticed as a carpenter around the time wheat farming began to surpass sheep farming as the main agricultural industry in southern Russian Mennonite settlements. With its spread rose the demand for farming implements, among them winnowing machines. Dietrich began manufacturing these and in time his modest shop in Osterwick in the Mennonite settlement of Chortitza (now a part of Dolynske, Ukraine) had grown into a factory that produced an array of farm machinery. By 1893, the year of the wedding, the factory machinery, which had initially been driven by a horse capstan, was now being powered by a steam engine. Dietrich had become a successful businessman. In time the factory would grow to employ some 100 men, in peak times as many as 150. This enterprise would ultimately come to be known as D.B. Schulz & Heirs, headquartered in Osterwick with branch offices in Kakhovka on the Dniepr River and near Omsk, Siberia.

Dietrich’s interests, however, were not limited to manufacturing machinery; he also took an avid interest in the community. Schooling was especially close to his heart. Having had little education himself, he must have felt the need for it all the more for the next generation and became the driving force behind the creation of a factory school in Osterwick for the children of the non-Mennonite workers.

Anna Wiens, also of Osterwick, would marry Dietrich Schulz in 1868 and bear him ten children, only three of whom would survive to adult age. The groom, Peter, was her second born and her oldest son. But, she would not live to see him wed. It would be her younger sister Margaretha, who would preside over the nuptials as Peter’s stepmother. Margaretha Wiens Koop Schulz had become a widow at age thirty-eight when her husband, Peter J. Koop, also a trained carpenter and successful entrepreneur, died in 1889. It was into her second marriage with Dietrich Schulz that Margaretha would bring half of the net wealth of the Koop Factory, which in turn would be amalgamated with Dietrich’s business to ultimately form D. B. Schulz & Heirs.

By the time Peter was betrothed he––thanks to his stepmother––had joined ranks with his younger brother Jacob and his stepbrothers, Jacob and Peter Koop, to manage the greatly expanded business. The large family enterprise brought together different branches of the intermingled family. The family was also to bear the costs of political violence that later engulfed the region. Of the four stepbrothers in business together, Jacob Schulz was banished to the Gulag in the 1930s without a trace, Jacob Koop was murdered 1928 by the ‘Urkagan’ (organized criminals) and Peter Koop who had become a minister after the Communists took control, was forcibly ‘taken away’ by the Communists in 1938. At the time of Peter and Anna’s wedding however, the large family enterprise seemed to be going from strength to strength.

The Zachariases

Not yet eighteen, Anna Braun had married the father of the bride, Isaak W. Zacharias in 1850. She would bear him ten children, six of whom would reach adult age. In 1864, Isaak, also originally from Osterwick, Anna, and his in-laws acquired land approximately forty-five kilometres northwest of Osterwick. At that time, the land was nothing but Russian steppes, pure frontier territory. But Isaak and Anna would rise to the challenge, as would Isaak’s second wife, Anna Bartsch Dyck, who would raise his children after Anna’s untimely death in 1880. The second youngest Zacharias daughter, Anna, the bride, was nine when her mother died.

By the time of Anna’s betrothal to Peter Schulz in 1893 her father had acquired all of the Braun interests and had become the sole owner of the estate (known as a khutor). Thanks to the seeds of Anna Braun’s hard pioneering work and relentless joint efforts with Isaak it had prospered greatly and was now called Zachariasfeld. By 1914 it would expand to encompass not only the wheat-growing business but also several lucrative ancillary businesses, such as a flourmill, an oil mill, wood working shops and, ultimately, a brick factory.

With these two proud Mennonite families uniting in Anna and Peter’s marriage, the stage was set for a grand wedding and a happy future.

To be continued…

Anna Braun Zacharias and Isaak Zacharias

Anna Zacharias Schulz (1871–1950) and Peter Schulz (1871–1914) in 1912.

Anna Wiens Schulz (1849-1890), mother of the groom.

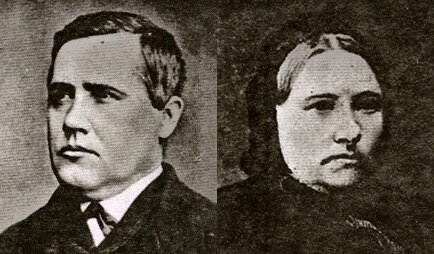

Dietrich Benjamin Schulz (1846-1908), father of the groom with Margaretha Wiens Koop Schulz (1851-1909), stepmother of the groom.

A map of Mennonite Communities in the Chortitza District, showing Peter Schulz’ hometown of Osterwick and Anna Zacharias’ hometown of Zachariasfeld